Tender offers were once a rare exception. Today, they’re a cornerstone of the private-market playbook. Tenders can be a powerful tool for retaining top talent and rewarding key stakeholders. Yet for many founders and employees, the process remains opaque: Who gets to participate? How much can you sell? How are prices set?

At NewView Capital, we’ve seen this play out firsthand. This year alone, we’ve led or participated in six tenders, with a seventh in motion. Analyzing our proprietary data on tender offers over the past few years, some clear patterns emerge that can offer a framework for founders and employees.

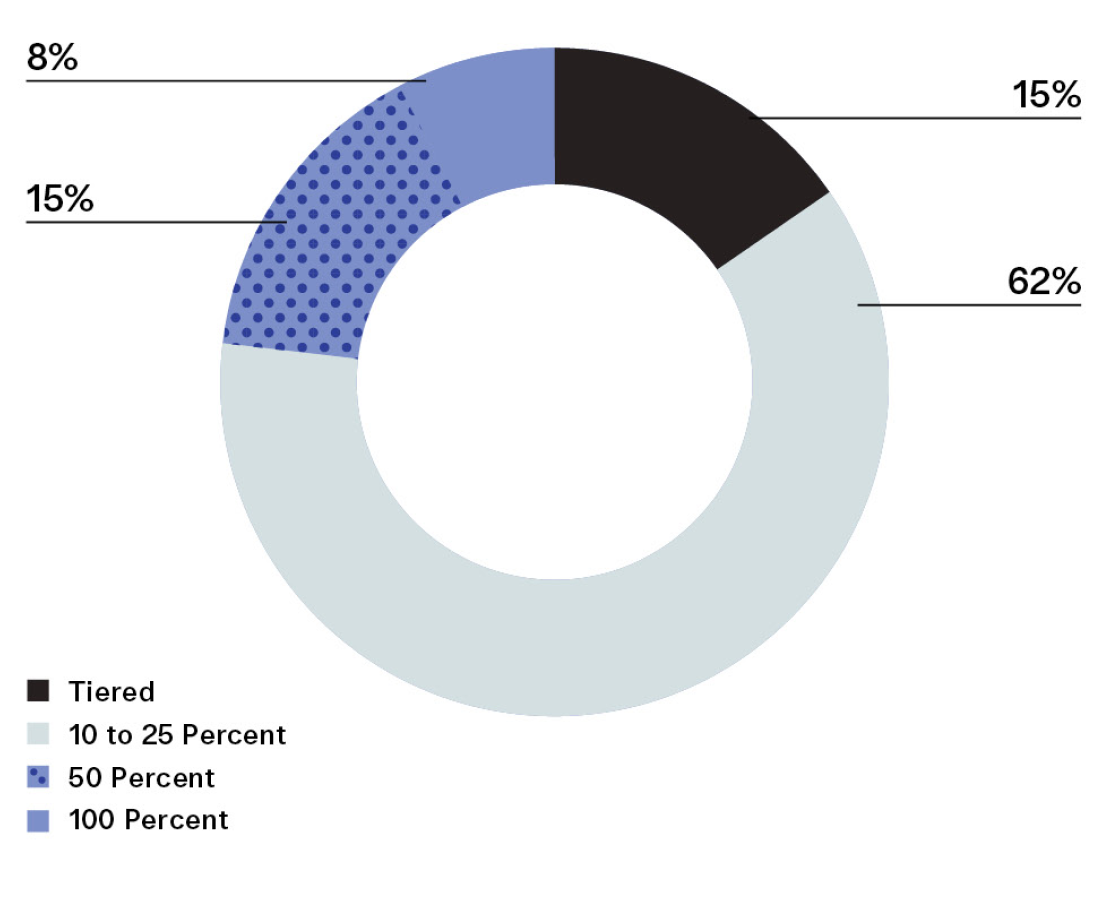

Who gets to participate?

62% of tenders we analyzed allowed former employees to sell shares. Including alumni creates goodwill and broadens access to liquidity. For example, Stripe has included ex-employees in past tenders, signaling that alumni contributions hold lasting value.1

However, it also raises a fair question: should liquidity only reward those still at the company? Or is there value in letting alumni cash out? In some cases, allowing ex-employees to sell can help bring new, long-term investors to the cap table who are less likely to sell six months after lock-up.

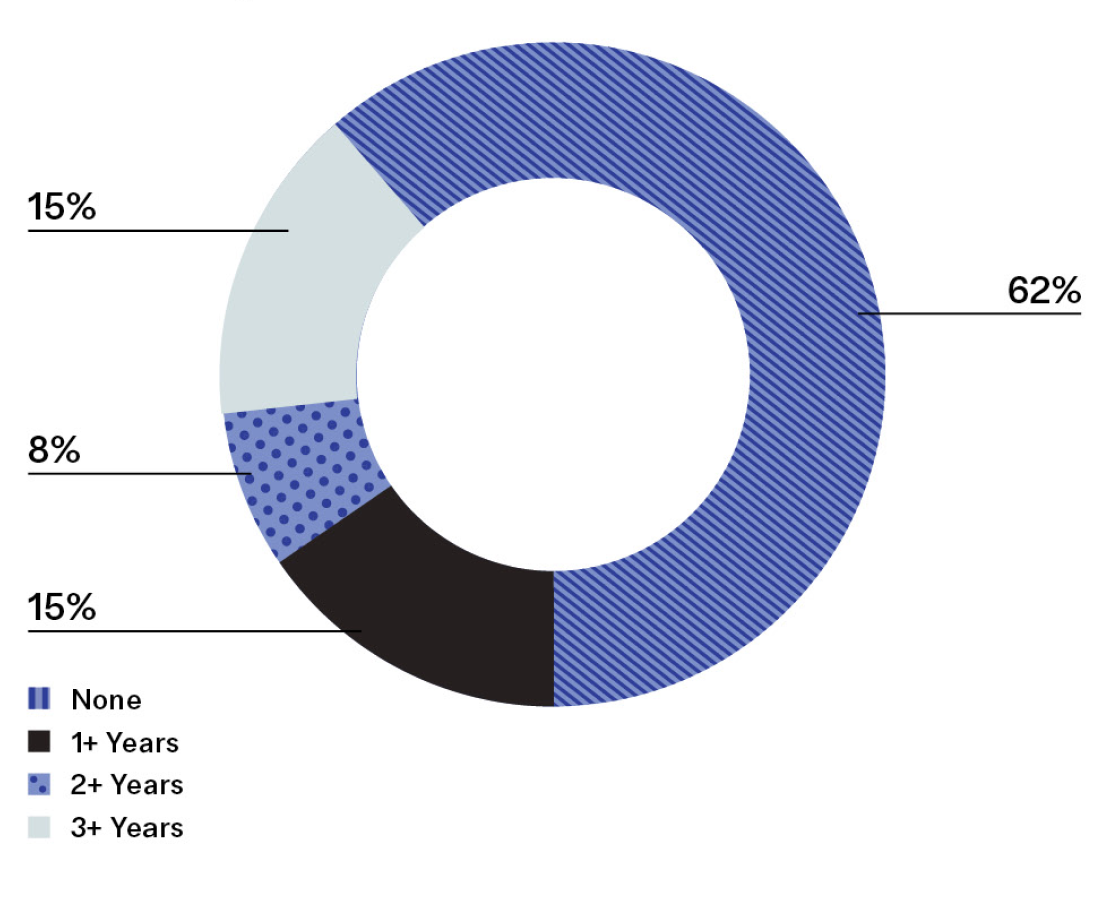

Are there tenure requirements?

Liquidity is no longer just for veterans. Only 38% of tenders had required tenure minimums. While some companies used tiered caps to reward long-tenured employees, most chose to include a broad base of talent, including newer contributors. When a tenure requirement was imposed, it was typically between 18 and 36 months of employment.

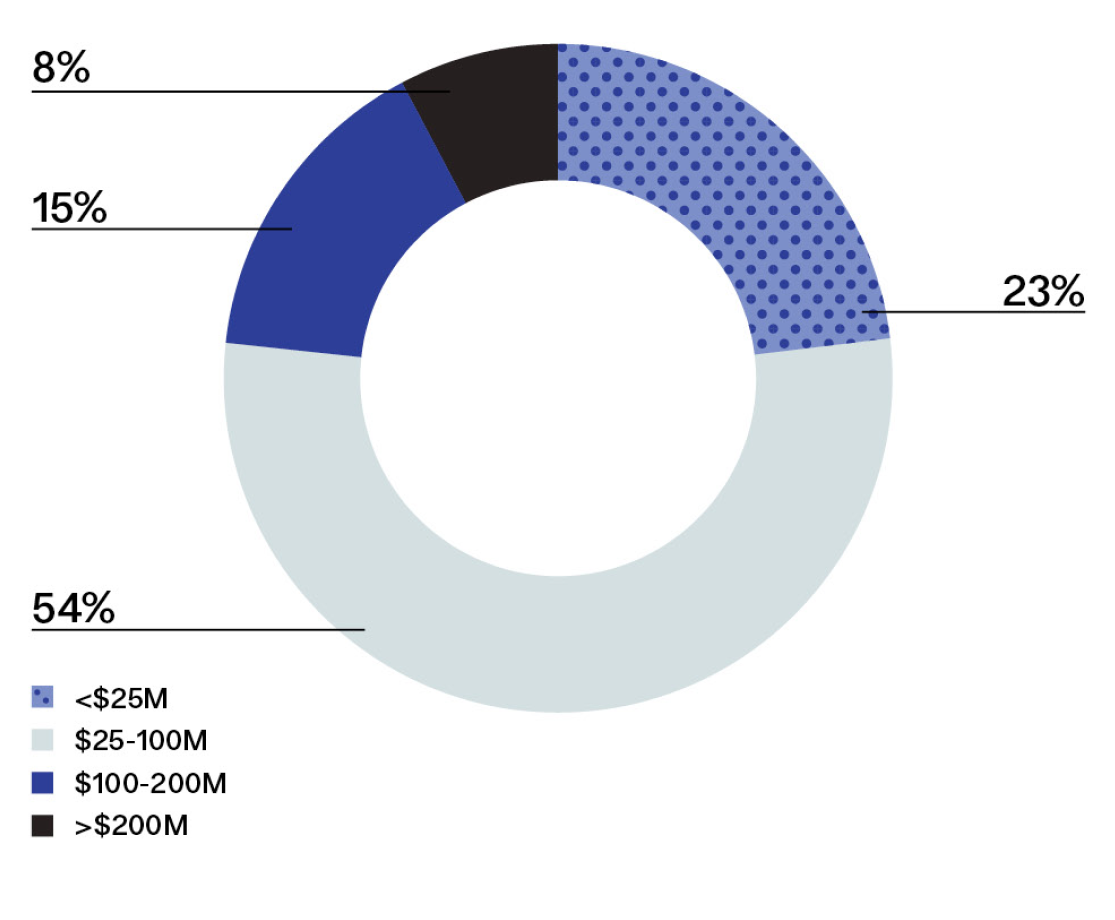

Do founders sell?

Founder liquidity is increasingly common, and we believe that’s a positive trend. Nearly two-thirds of tender offers we analyzed included founders. Allowing founders to reduce personal risk helps them stay focused on building for the long term, instead of feeling pressure to cash out early. Of note, our data shows that founders were typically subject to stricter caps on the percentage of holdings that they could sell.

What about early investors?

46% of tenders included preferred holders. Some companies restricted liquidity to employees doing the day-to-day work. Others preferred the simplicity of a single annual liquidity event that enabled them to manage the composition of the cap table.